Topic outline

- General

- Topic 1: Language and Linguistics

Topic 1: Language and Linguistics

Topic 1 Post Test Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 1.5 Conclusion is marked complete

- Topic 2: Phonetics

Topic 2: Phonetics

Topic 2 Pre Test

Topic 2 Post Test Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Topic 2 Pre Test is marked completeTopic 2 Post Test

Introduction to Phonetics

- Topic 3: Phonology

Topic 3: Phonology

Topic 3 Post Test Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Topic 3 Pre Test is marked completeIntroduction to Phonology

- Topic 4: Morphology

- Topic 5: Syntax

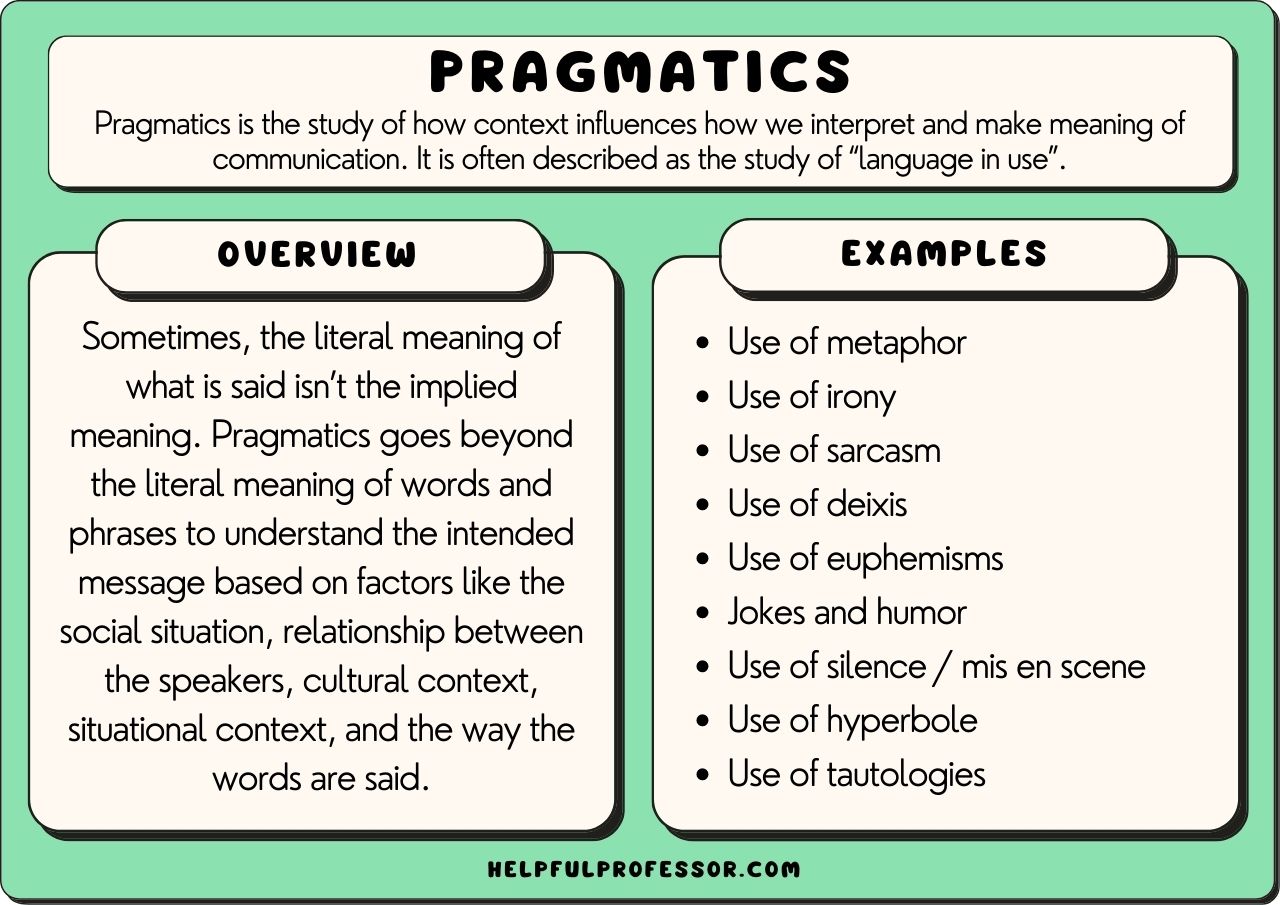

- Topic 6: Pragmatics

Topic 6: Pragmatics

Post Test Topic 6 Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Pre Test Topic 6 is marked complete

- Topic 7 : Stylistics

Topic 7 : Stylistics

Post Test Topic 7 Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 7.1 Introduction to Stylistics is marked complete7.2 Levels of Stylistics Analysis Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 7.1 Introduction to Stylistics is marked complete7.3 Literary Devices and Foregrounding Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 7.2 Levels of Stylistics Analysis is marked complete7.4 Genres, Register and Authorial Styles Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 7.3 Literary Devices and Foregrounding is marked complete7.5 Computational and Corpus Stylistics Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 7.4 Genres, Register and Authorial Styles is marked complete7.6 Conclusion Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 7.5 Computational and Corpus Stylistics is marked complete

- Topik 8: Mid Term Exam

Topik 8: Mid Term Exam

#UTS (Evening Class) Quiz

Restricted Not available unless:- You belong to Semester 2 Evening Class

- It is before 17 May 2025, 11:55 PM

MID TERM TEST Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: You belong to Semester 2 PAGIMID TERM TEST_REMEDIAL Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: You belong to Semester 2 PAGI

- Topic 9: Semantics

Topic 9: Semantics

Post Test Topic 9 Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Pre Test Topic 9 is marked complete

- Topic 10: Systemic Functional Grammar

Topic 10: Systemic Functional Grammar

Topic 10 Post Test Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Topic 10 Pre Test is marked complete

- Topic 11: Sociolinguistics

Topic 11: Sociolinguistics

Topic 11 Post Test Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Topic 11 Pre Test is marked complete

- Topic 12: Psycholinguistics

Topic 12: Psycholinguistics

12.2 Core Components of Language Processing Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 12.1 Introduction to Psycholinguistics is marked complete12. 3 Major Sub-fields of Psycholinguistics Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 12.2 Core Components of Language Processing is marked complete12.4 Prominent Theories and Models Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 12. 3 Major Sub-fields of Psycholinguistics is marked complete12.5. Research Methodologies and Practical Applications Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 12.4 Prominent Theories and Models is marked complete12.6 Conclusion Page

Restricted Not available unless: The activity 12.4 Prominent Theories and Models is marked complete

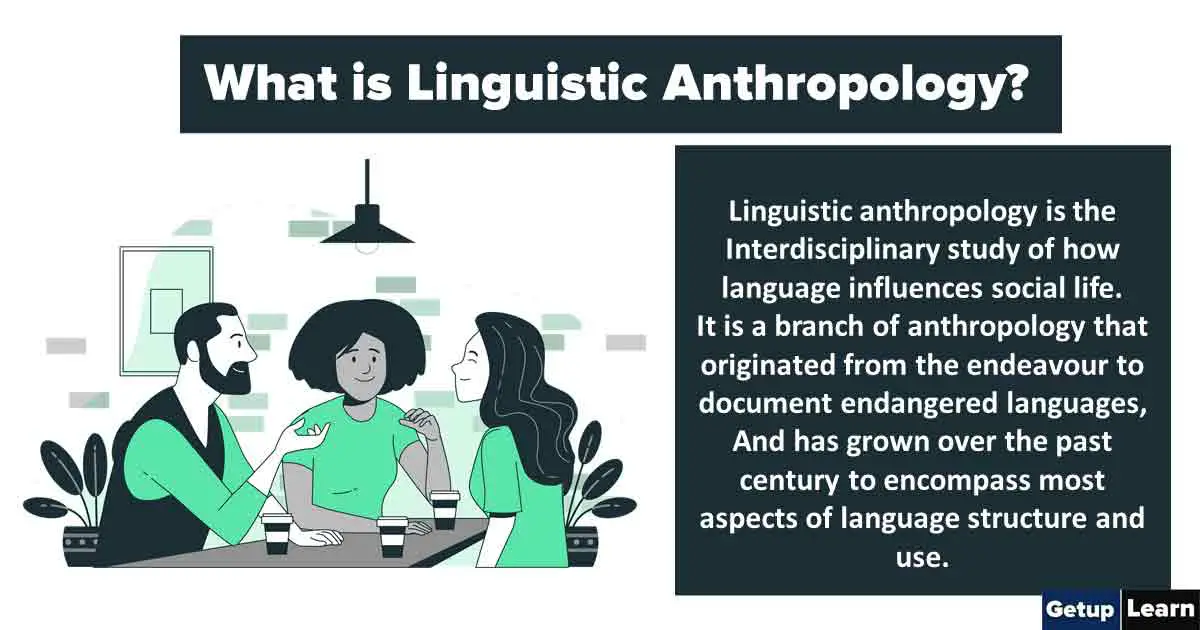

- Topic 13: Anthropolinguistics

Topic 13: Anthropolinguistics

Post Test Topic 13 Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Pre Test Topic 13 is marked complete

- Topic 14 Discourse Analysis

- Topic 15 Ecolinguistics

Topic 15 Ecolinguistics

Post Test Topic 15 Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: The activity Pre Test Topic 15 is marked complete

- Final Test (UAS)

Final Test (UAS)

FINAL TEST SEM 2 PAGI Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: You belong to Semester 2 PAGIFINAL TEST SEM 2 EVENING Quiz

Restricted Not available unless: You belong to Semester 2 Evening Class